Source: European studies blog

Raising Kurdish Armenia: Kurdish Children’s Books from Soviet Armenia – Asian and African studies blog

First Impressions: The Beginnings of Ottoman Turkish Publishing – Asian and African studies blog

My first big step

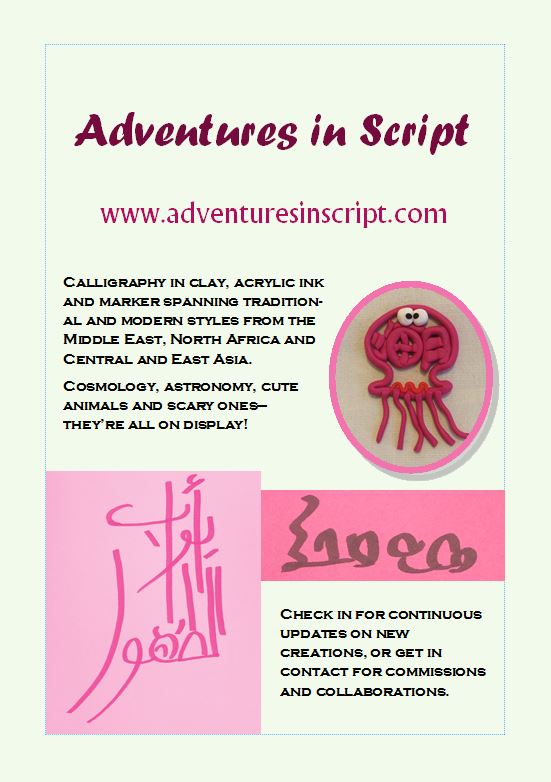

I suppose that I started this blog, and the various projects that I’ve been working on besides the blog (and my day job) as a hobby. I never really expected to devote as much time and energy into creating and promoting, but the fact is that it really is quite fulfilling.

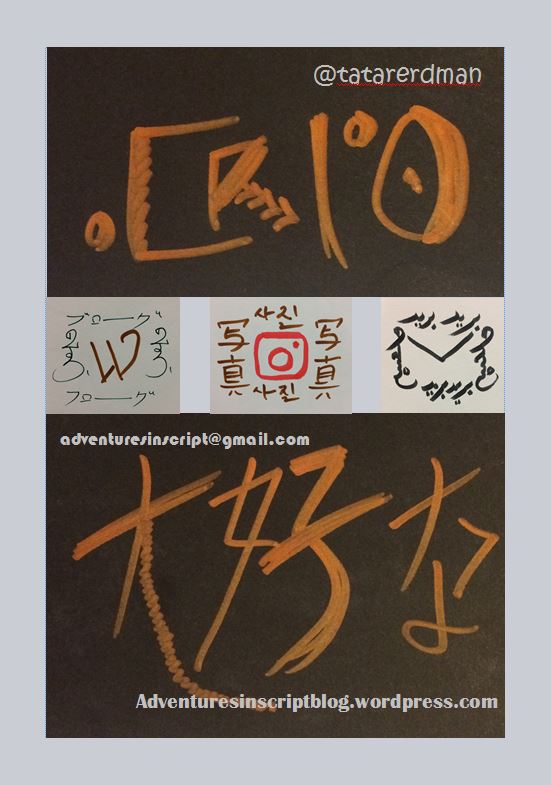

That’s why I’ve decided to take a big step and move off the web. That sounds a bit wrong, since it sort of sounds like I’m abandoning my internet activities for offline stuff. Actually, what I mean is that I’m going into the offline world in addition to my various projects online. I’ve created my own flyers and sent them off for printing. There are only 25 of them, but it’s just a first step. Still, I’m hoping that it’s a positive one, something to help bring more people to my various websites, blogs, and Instagram account (@tatarerdman), and to engage with other lovers of language and calligraphy.

Take a look and feel free to comment (or better yet, visit)!

Pop your linguistic cherry

Sex sells, they say. Sex is… well, sexy. Thank you for the tautology, you’re probably thinking right now. Perhaps this was a bit on the obvious side, but when talking about sex we often get lost in the commentary about what is natural and what isn’t; what is decent and indecent; what is liberating and oppressive – and we forget to think about our most basic attraction to the act. In part, I think that sex draws us in because we are so fascinated by reproduction. By that, I don’t just mean “making babies”, since so many of our sex acts would never result in the fertilization of an ovum by a spermatozoa. Reproduction isn’t just about making new humans: it’s also about replicating relationships, emotions, states and memories that well up inside us and seek out a release, like churning waters surging against a dam.

There’s another aspect of our lives that relies heavily on reproduction too, and that’s language. Language reproduces in so many different ways. Its entire functionality rests upon our ability to replicate items and structures that we have heard before and that form a corpus of a shared and widely accepted items used by a community to express their thoughts and emotions. Occasionally, we use it to reproduce an event as well, as we try to manipulate the words and phrases at our disposal to create an impression amongst our listeners. Language is also a tool of top-down reproduction, as governments and state bureaucracies employ it to encourage the continuity and replication of the structures and relationships that bind together our societies and our polities. I’ve written about this in a much more academic way in the Early Stage Researchers’ Journal. And of course, language comes into that ever-so-sought-after font of reproduction, sex.

Sex and language are intertwined in many different ways. In sex, language taps into a powerful and energetic source of creativity and change. Words and phrases take on new connotations, both pejorative and approbatory. A friend of mine once said “Basically, in Italian, everything means cock.” To a certain point, that’s true for any language, with the caveat that the same word can’t mean cock and pussy at the same time. We are so focused on and enthralled by our connections to sex that, with a little elbow grease, we can repurpose any word or phrase into a titillating and slightly embarrassing reference to our baser needs and desires. Sometimes these are euphemisms, and sometimes they’re exactly the opposite: raunchy, dirty phrases that make us blush, wet our panties or get rock hard.

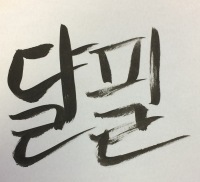

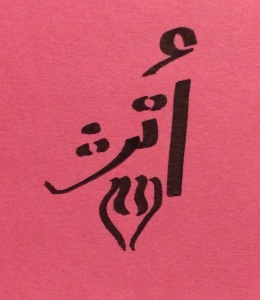

So if language is reproduction, and sex is reproduction, why not combine them into the ultimate mimetic experience: art? I’m quite a fan of calligraphy and other creative endeavours that involve language in both its semantic and visual forms. I’ve incorporated language into all sort of different media on my website: Fimo animal figures of Japanese kanji; cute Arabic and Persian letters in clay; acrylic explorations of planets’ names and funny phrases; and a marker take on traditional calligraphy from Japan and Korean all the way over to Cherokee and Inuktitut syllabics. In this case, why wouldn’t I take the logical step and combine this with another type of reproduction: sex. No, I’m not going to take up some sort of linguistic pornographic art (in the sense of pornography as defined by Susan Sontag, as something that appeals to the visceral rather than the emotional and intellectual). Rather, I think it apt to juxtapose the visual and the textual in order to highlight the manner in which language and sex are bound up together in our obsession with reproduction. A pen, a brush, a chisel or a knife – they’re all phallic, penetrating and massaging and altering the receptive paper or clay. They help us to impart our emotions, needs and desires into the fertile medium, mother and nurturer of expression and creativity.

Please enjoy these images that combine the throbbing, all-consuming urges of my psyche and libido. Whether they get you thinking or get you stroking, I’m rather ambivalent. I just hope that they make you reflect a little on our complicated and complex relationship with sex, love, language and life.

And hey, after all, who doesn’t like to be titillated from time to time?

Scratching the Surface: the Runic Imaginary – European studies blog

Why I love Tintin

My first exposure to the world of Tintin – the famous cartoon reporter of Belgian author Hergé – was in French class at age 9. Tintin was an icon of Francophone culture, a hero of inquisitive young people and nostalgic adults alike. For the next five years, I associated him exclusively, and erroneously, with France, its language and its modern history. When I was 14, however, I traveled to the Basque Country with my father, and there I found something that fascinated me: Basque translations of Tintin. I bought copies of Flight 714 to Sydney and The Tournesol Affair, and thus began my multilingual Tintin collection.

Since my first acquisition, I have accumulated 14 more titles in 12 languages: French, Spanish, Catalan, Hungarian, Turkish, Arabic, Persian, Japanese, German, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh. Some are very common, while others are quite rare. My Arabic copy appears to be unauthorized. Others, such as the Spanish and French versions, are available in any major bookstore in Madrid or Paris.

Tintin is both the clichéd hero of childrens’ imaginations, and the unique product of the life and work of his creator, Hergé (the alias of Georges Prosper Remi). As Tom McCarthy’s work Tintin and the Secret of Literature wryly explores, behind the adventures of the young reporter, his dog Snowy, and a cast of buffoons, clowns and villains, lie Hergé’s hopes, anxieties and disappointments. Abandonment, latent homosexuality, frustrated grandeur and visions of success are all palpable in the otherwise trite shenanigans of an overly curious young man who travels to countries near and far, real and imagined.

Hergé’s work is characterized by idiomatic and pregnant language, and multiple versions of the same comic allow me to compare translation strategies in dealing with his expressive style. As many of these editions were produced without the author’s input, it is a fascinating study of whether the translator caught the author’s intention and, furthermore, whether she found it appropriate, or possible, to convey it in the target language. It is more than just Hergé’s neuroses, however, that need to be transferred. So too must Tintin’s, and Hergé’s, sordid pasts, replete with examples of colonialism, racism, misogyny and fascism. There is no escaping the blatant inferiority with which characters of colour are imbued in works such as Tintin in Congo or Tintin in Tibet. Nor can one ignore the stereotypes inherent in the greedy but stupid Rastapopoulos and the flighty, vapid Bianca Castafiore. How does one carry such concepts into languages and cultures in which they do not exist or, worse yet, against whose speakers or members they are directed? Does the act of translation then become one of subversion, or is it merely submission to the hegemonic discourse of the metropole? These issues are tackled in different ways in different environments, from Basques in San Sebastian to Egyptians in Cairo, and their strategies all come together in my modest collection of the perils and pleasures of a boy and his dog.

Şəhidlər: Azerbaijan’s Black January – Asian and African studies blog

Thanks for the Memories

“Did you process the request for a driver’s license for Louis-Phillippe?” I asked Yashar, already aware of what the answer should be.

“Yes, yes,” he brushed me off.

“Really? Why isn’t it showing in the online system then?” I pressed further, confident that this would be the unfulfilled request that would break the camel’s back.

“Oh, you mean in the computer? No, I didn’t. I just took it and wrote out the forms. They’re in my drawer,” Yashar clarified, as if this were the same as logging a request in the online system.

“So then you didn’t do it, since you haven’t been able to request a license conversion by paper for years, and you never entered anything into the online system,” I said, gloating ever so slightly, but also acutely aware of the shitstorm I was in for when I told Louis-Philippe his license was still not ready.

“Why are you always so difficult!” Yashar suddenly complained, edging closer to that state of emotional excitement I knew would end in tears.

Two years. That’s all I told myself I needed to do, and then I’d have another posting. I had joined the Foreign Service the year before, and, since I had already learnt Arabic, I decided to fast-track my career by taking the post that no one else wanted: Riyadh. I was self-sure, convinced of my ability to learn quickly; my drive and perseverance; my efficiency and steely nature in the face of adversity. In short, I was a pigheaded idiot who thought, at 27, that he could change an entire organization and break a culture of complacency through will alone. It took about 10 days for me to realize just how deep in shit I was when I arrived, and about 13 days before I started wondering if it was too late to change careers from diplomat to shepherd in the Pyrenees.

Riyadh was sort of the Melrose Place of the Canadian diplomatic Los Angeles. The Embassy was a mess of intrigues and feuds, largely stemming from a sexual harassment case a few years earlier. This was coupled with not one but two allegations of affairs and/or impropriety between Canadian and local staff, and a level of incompetence that made George W. Bush look like a brain surgeon. Just to be clear, Melrose Place works when there is only one Heather Locklear; if everyone thinks she or he is Amanda, we won’t even make it to the end of the pilot, let alone a full season. Somebody has got to be Allison the Loser, Billy the Jock or Michael Mancini the Stupid Philanderer. That’s how these things work.

I don’t really know where Yashar fit into the cast. His replacement, Ala, certainly did as Sydney, Michael’s sister-in-law, but there wasn’t exactly a bumbling old fool whose place Yashar could take. He had been at the Embassy for nearly 37 years, first in Jeddah and then in Riyadh, and had really been a great member of the team as a gopher, when gophers were still gophers. Times change, though, and the computer revolution means that we can all sit around and get fat while sending off requests by email, rather than chasing them around on foot. Unfortunately for Yashar, the digital age sort of passed him by, and he was clinging to his job through sheer will, long-lasting friendships and inertia.

Then I arrived. My boss had given me the task of seeing Yashar off, either through retirement, firing or a catapult. Apparently, he had angered someone when he forgot to clear the Ambassador’s shipment of personal effects, and the man had been told to spend three months with the same four pairs of underwear. Who knew the Ambassador would be so touchy?

“Yashar, this is a meeting to discuss your performance. It’s been lackluster the last few months, and I want to make sure you’re performing according to your job description.” This was the first step. I had to call a meeting to discuss Yashar’s performance, put him on a plan and – when he failed, which I was sure he would – I would fire him. Who knew destroying a grown man’s will to live could be so straightforward?

“No, it’s a trap,” Yashar snapped.

“Um, no… The agenda clearly says performance management,” I tried to bring the meeting back on track.

“Everyone here has treated me badly. I’ve had so many things done to me…” Yashar started off on the usual litany of hardships and tests, conveniently forgetting the time the Ambassador had to go commando because he couldn’t be bothered to click Send.

God, I thought to myself, this is never going to end. Can I still make it to the swimming pool after work? Am I going to be having the same thing I always seem to have for dinner – a Subway sub and a bag of peanuts? How many more hours do I have before my time in Saudi ends? 13 000?

“So that’s why I can’t sign anything. You see, Jean came into my office three years ago…” Yashar was still going. It was like this was the only thing he had energy to do.

“Michael, there’s something heavy in the diplomatic bag for you.” Mail day was always a good day. It was when important things, like replacement credit cards and New Yorkers arrived. Apparently it was also when things from Ottawa that I didn’t know would be coming also showed up.

I was now a year into my posting, and I was very much a changed man. Angry, bitter, but mainly a hell of a lot fatter. I had learned to deal with some of the stress of the job – usually by eating – but there were lots of sore points still there, like those little flecks of pasta sauce you can never get out of a white shirt. One of them was Yashar.

Yashar and I had come to an understanding: we hated each other. For Yashar, I represented years of pressure and boorishness on the part of the Canadians. For me, Yashar was a distillation of everything that was wrong with the bureaucracy and the way that everyone in the Embassy cared more about gossip than getting stuff done. I had done nearly a dozen performance meetings with him, disciplinary hearings and general dust-ups that seemed to thwart my one and only desire: to see his position vacant. We were nearing the end of the road, though. I could feel it. One more meeting, one more screw up, and I’d be able to fire him. I knew it. He knew it. We all knew it.

“What’s in there?” asked Buzz, our Military Policeman and the one who handled the mail bags. Buzz was your typical Canadian soldier: out of shape, a heavy drinker and smoker, racist, sexist, plaintive and generally an eyesore, but endearing enough to the right people to keep on in his position. I normally wouldn’t stomach people like Buzz, but I needed every ally I could get, so I held my nose and swallowed hard, like I would for durian candy.

“I don’t know. It’s something from HR, something…. Oh, for fuck’s sake!” I exclaimed while opening the package. “It’s a plaque for Yashar – for 35 years of service. I can’t fucking believe that I have to give him this!” I was beside myself. I had become significantly balder trying to convince Yashar that he wasn’t up to doing his job and should just retire, and now I was supposed to thank him publicly. My fucking luck.

“HAHA,” laughed Buzz, “I’ll bring some popcorn to the ceremony!”

Yea, you’ll enjoy it plenty, won’t you? I thought. Jerk!

That was it. I had finally got him. Yashar had totally botched a request for an exit visa, and I had documented the whole process of finding out just how. I knew that this would be enough to nail him down. Logically, I could see that this was absolutely evil. To have someone who has worked 37 years be fired for incompetence meant depriving them of their pension, and that seemed toxic. But I wanted to get rid of him. I wanted to get on with my life, to get on with my work and to get the hell out of Saudi. I had called a disciplinary meeting for Wednesday, but first we had to do the award ceremony on Monday. It was going to be done at an all-staff meeting, where I would present the award to Yashar in front of 40-odd people.

“And finally,” I said, “we’re here today to celebrate someone who has been part of the Embassy for over thirty-five years. Someone who worked with us in Jeddah, who followed us to Riyadh, and who remembers more of this Embassy’s history than anyone else.”

So far, so good. I was usually good with BS, and I didn’t see why my talents should fail me now. There was only one sticking point. I couldn’t bring myself to thank Yashar for his work. I had spent a year telling him how awful it was. How could I now stand here and lie – while smiling, no less – to the whole group?

“And so, to Yashar, who has been part of the Embassy family since 1973, we say:” The sweat was heavy under my arms, and was starting to build up along my forehead. I was sure this would be the moment I had that aneurism I was convinced would kill me.

“Thank you…. For the memories.”

You Gonna Eat That?

“I want you to meet my ex,” Mehmet said to me. “He’s not like you. He’s really sensitive and fragile and although it didn’t really work out between us, I still care for him as a friend.”

Didn’t really work out between us? What the hell does that mean? It didn’t work out between you. That’s why we’re together. Otherwise you’d be together. You can’t date people in ratios.

“Oh, ok, I guess. But just for a meal or something, right?” I answered, doubt and insecurity dripping from my response.

“Yea, great. We’ll go somewhere in Shoreditch for Vietnamese. You’ll really like it!” Mehmet chimed in, willfully oblivious to any emotion in my answer.

Mehmet and I had met at our university gym, where he worked out and I would go swimming. That is, where he would go to be seen on the elliptical machines and hopefully pick up, and I would go swimming. That is, we passed each other on the way to the water fountain and then chatted on Grindr two days later. The exact chronology isn’t important; the fact of the matter is that he was my first boyfriend in London after I had moved here from Canada. He was entirely part of my new life as a Masters student in Turkish Studies. He was lefty, a PhD student, Azeri, a hipster, into (at least the idea of) keeping fit and a full-fledged Londoner. He was also seven years younger than me, and about a light-year less mature, which I worked hard to ignore.

Mehmet was pretty social. By which I mean that he had a fear of intimacy and one-on-one interaction not in the form of sex. A week didn’t go by when an alleged date for just the two of us suddenly had a new chum, acquaintance, friend, buddy, pal or just stranger off the street joining us for beer or food. I’m at the other end of the spectrum, and like my groups to be, well, minimal, so I guess I never really got comfortable with Mehmet, or opening up to him. Not that he would have listened to anything personal I had to say that didn’t begin with the phrase “Beyoncé really speaks to me because…”

We had agreed to meet at 7 at Hoxton overground stop, and then head on to the restaurant, which was around the corner. When I got there and found Mehmet, he told me that Davo, his ex (who should have started calling himself David about 20 years ago), would be about 15 minutes late.

“He’s probably working on something super important. He does all sorts of stuff like designing club nights,” Mehmet prattled on.

Yes, I thought, he’s probably stuck at the hospital clearing a blocked artery, or tending to the poor and destitute of Kolkata, like a modern-day Mother Teresa with an active sex life.

“Oh, that’s fine. Can we get some starters or something?” I said, trying to console myself.

“Of course not! That would be sooooo rude, Michael! We’ll wait for him to come before we get a table.” Mehmet was always so considerate for people who didn’t form part of the relationship.

Davo arrived 20 minutes late, evidently not from the office.

“Sorry, I totally got caught up with something I was watching on YouTube. A great set of music videos.”

“Oh my God! Beyoncé? MIA? Who are you into now, Davo?” Mehmet was beside himself with joy from the opportunity to find more pop idols to mimic in his daily life.

“MIA. She’s so meta. She reminds me of what I really want to accomplish in my life. I just feel so…. Sorry, I can’t talk about it, it makes me too emotional.” Davo suddenly choked up like a little boy who’s been told Old Yeller won’t be coming home.

“Of course, Davo. Oh, remember how we used to always joke about the way people used ‘literally’ wrong? Like, they would say that ‘he was literally on his way’, as if they were talking about a book or something. HAHAHAHA.” Mehmet was trying hard to keep Davo on the up.

“Do you think the Pho Hanoi is good? I feel like something hearty. Is that hearty?” I asked, trying to bring the conversation to just about the only thing during the evening that would interest me, the food.

“What?” Mehmet suddenly realized that I was there. “Um, yea, sure, order whatever you want.”

The night progressed, slowly. Most conversation chunks started with the phrase “Remember when we…”, which naturally meant I was left to shovel my food into my snout, or conjugate Turkish verbs in my head while pretending to be listening. Mehmet and Davo were too busy chatting to pay attention to their food, and my hunger was being fed by boredom and exclusion, despite the copious amounts of rice and beef I was cramming into my stomach.

“So, Michael’s looking to move in a couple of months,” Mehmet suddenly announced, as if this were a pre-arranged interlude. “Maybe he could live on your boat and watch it for you while you’re in Ibiza this summer.” I suddenly remembered that Mehmet had said Davo lived on a houseboat on Regent’s Canal not far from Shoreditch High Street. Also, that he occasionally had drug-fuelled sex parties with randoms he picked up on Grindr or Scruff or Growlr or a street corner. There were so many things that made me shudder when thinking about the suggestion, but, ever concerned with keeping Mehmet happy, I smiled and perked up, as if I had actually wanted him to suggest this.

“Nah,” Davo brushed off the offer. “I’d prefer not. I don’t really know what’s going on this summer, and, you know, I’ll probably be in and out of London anyway.”

“Oh, really? Hey, you should have another one of those parties like you used to, Davo.” Mehmet was now off his brilliant idea. “Remember, like the one where I wore those glittery high heels the entire night…”

Oh, for fuck’s sake! This was like being in that scene from Primary Colours when they go on about their mammas, but far less entertaining, and with much less food.

Another hour of this. A long, boring, senseless hour of reminiscences and in-jokes, most of which made me want to get up and scream “Take my wife – please!” and hurl Mehmet at Davo. The only thing that kept me looking over at that side of the table was Davo’s nearly untouched bowl of broken rice with chicken. I wanted it. I wanted it bad. I wanted it like I wanted to turn back the last three hours, avoid coming out to Shoreditch and spend my night reading Tintin comics, eating yoghurt and granola pots and lying around my room in my boxer shorts. It was so close, and yet so, so far away.

“Have you been dating anyone recently?” Mehmet finally got to the question that I knew he had wanted to ask all along. He wasn’t really interested in showing me off to anyone, just in showing them that he had a boyfriend, like a trench coat or a beanie that he wore in the height of May heat. Similarly, he wasn’t all that interested in Davo, he just wanted to know that he was, in some perverse way, irreplaceable.

“I’ve dated a couple of guys, but it’s just so hard. You know, people are so judgmental on the apps. They like, say all this stuff about not being into this type or that type, and they don’t get to see the real me,” Davo started complaining.

Yes, I thought, why can’t they see your deep and interesting personality after the cock shot? What is it about these youngsters that they don’t know how to build a close connection through an impersonal communication portal? And what the hell is going on with your meal? Who the hell orders something as delicious as that and just lets it sit there, awaiting its final end in a rubbish bin, or, more likely, the bowl of the next diner to order broken rice with chicken.

“I mean, it’s so hard. I just… Sorry, it’s getting me all emotional again…” David was on the verge of another scene from Bambi, and I was at my breaking point.

“Hey, uh, Davo, you gonna eat that food? Because it seems like you’re done with it, and I’m still kinda hungry…” I seized my chance. I would redeem this evening in some way.

Mehmet glared at me. Davo stared in slight disbelief. And I smiled – genuinely, for the first time all night – as my chopsticks reached across the table to grab that fatty piece of meat.